A voyage to the northern Gulf of Mexico

Early in February (what now seems like eons ago!), during less infectious times, we went out to sea in the Gulf of Mexico. I’ve written before about our sediment trap project and the papers stemming from it. Unfortunately, however, this trip was the last one under the current funding regime, and our job was to ensure that both our traps came back up to the surface (which they did); we would not be redeploying them. Womp womp. However, we are working towards getting more funding so we can continue monitoring Gulf of Mexico sedimentation (and foraminifera!)

The Gulf of Mexico is an important oceanic body of water for the United States and Mexico for several reasons; climatically, it is an essential moisture source. Sea-surface temperatures in the Gulf can have a significant influence on rainfall and atmospheric circulation over a large swath of North America. It also serves as the ultimate sink for the Mississippi and other large river systems of the US and Mexico. Naturally, you can imagine that the record of sediments preserved in the Gulf of Mexico holds many crucial histories of North American climate change and the myriad of interrelated tales concerning paleoecology, paleoanthropology, archaeology, etc. Of course, some of these secrets have already been unearthed: stories that detail the extent of Laurentide Ice-sheet meltwater routing, mysteries of abrupt climate change, oceanographic implications of cometary impacts, Little Ice Age hydroclimate, and so on... but there are many others in the making and indeed, many more yet to see daylight.

An animation depicting daily sea-surface temperature variability in the Gulf of Mexico from 2012-2013. Notice that the structure of the Loop Current is visible in the temperatures! If you pay attention, you can also see an eddy pinching off. This animation was taken from the Naval Oceanographic Office website.

But the paleoclimate tales yet-to-be extracted from the Gulf of Mexico are not limited to histories of terrestrial climate change. Oceanographically speaking, the Gulf is highly dynamic - featuring the Loop Current and its energetic (and enigmatic!) process of shedding “eddies”. The Loop Current transports warm and salty waters from the Caribbean Sea through the Yucatán Straits into the Gulf and “loops” eastward, exiting outward through the Florida Straits. While doing so, at times, giant (multiple-kilometer-wide) swirling masses of Loop Current waters (eddies) “pinch off” the primary current and flow westward into the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. These warmer waters have unique parameters (oxygen, salinity, etc.) and contrast with cooler, fresher coastal waters. These eddies are very important for the wellbeing of marine ecosystems in the Gulf. They can also act as heat engines for hurricanes that pass over them (as in Katrina). There’s a lot of debate about the future of the Loop Current and its eddy-shedding system with ongoing anthropogenic warming. I’d argue that paleoceanography is hugely important to this endeavor as reliable observations of these processes are highly limited.

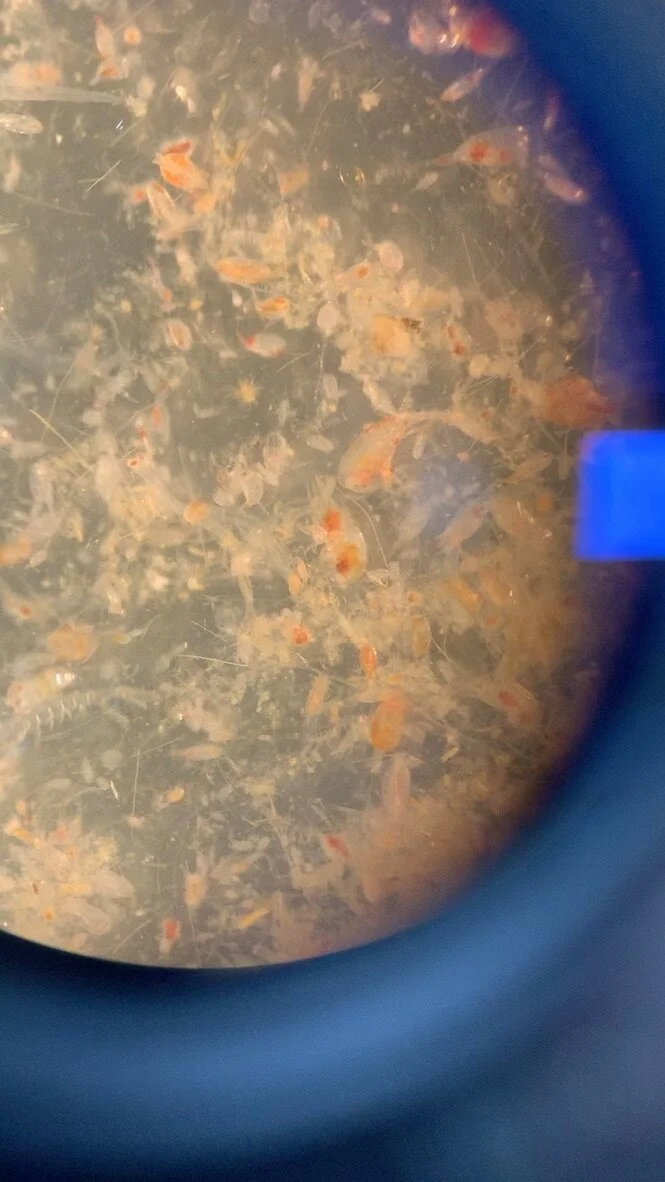

Foraminiferal shells housed in the Gulf of Mexico have the potential to tell these stories. Through their species distribution as well as several chemical signatures stored in their calcite shells, “forams” are important indicators of past oceanic processes. This time around, we were interested in collecting specimens of Globorotalia truncatulinoides. We think this is an ideal species for reconstructing winter climate conditions and wanted to see if we could culture some individuals. Towards this, we dragged a plankton net at a water depth of ~80 m (the truncs live in the sub-surface ocean) and collected many planktic species. Overall, I think we were quite successful, and many of those collected individuals are still alive today (well over a month from the time of collection!)

Here are a couple of photographs from our plankton tow:

And remember things can get rather rocky when you are out to sea and looking under a microscope!